When Darlene Belden woke up in the middle of the night and felt pain in her arm, she started considering possible causes.

“I’d gone to the corn maze that day with my kids and grandkids, and I’d carried this purse around all day. I thought that’s what it was,” the 71-year-old Redmond resident said. “Or I thought maybe I’d eaten a funnel cake that gave me food poisoning.”

Belden never connected the pain to her heart, in part because she had no history of heart problems. Fifteen years earlier, she said, she had been tested for blockage in her arteries and came back clean. She repeated the test six years ago after her sister died of a heart attack. Again, she said, doctors found no evidence of plaque buildup.

“A heart attack did not even enter my mind,” Belden said.

But Belden had, in fact, had a heart attack. She just didn’t know it, and a subsequent visit to her primary care physician didn’t uncover it. Eventually, she went to urgent care, where a provider ordered an EKG and, concerned about the results, sent her to the hospital. There, an Emergency Department physician ordered Belden an echocardiogram – an ultrasound of the heart.

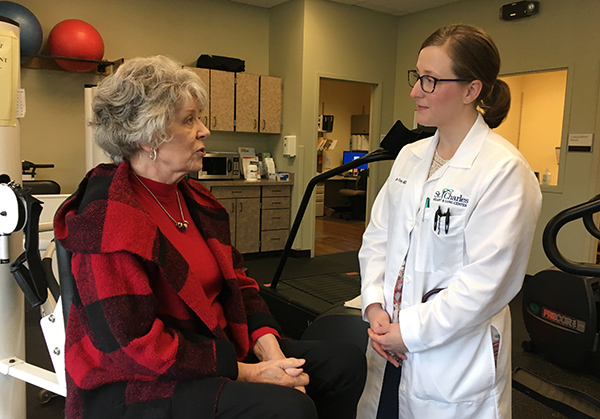

And that’s when Belden met Dr. Jillian Foley, who was on call that day and reviewing echoes. Belden’s test results showed a heart attack and a blood clot in her heart, Foley said, so she went to meet the woman and admitted her to the hospital for further evaluation.

Foley, a Chicago native, is not only St. Charles’ newest cardiologist, she’s also the health system’s first-ever female cardiologist. She says stories like Belden’s are far too common, and they highlight the differences between the way men and women experience heart disease, and thus the differences in the care they receive.

For example, women generally seek health care for heart issues about 10 years later in life than men, Foley said, and they have more risk factors than men when they do seek care – simply because they’re later in life. That passage of time also leads to a greater prevalence of diastolic dysfunction – a stiffening of the heart – in women, as well as an increase in comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes.

Women also often face a delay in diagnosis of heart disease because of atypical symptoms, said Foley, who moved to Central Oregon last fall. Chest pain is the most common symptom for both men and women, but women are more likely to have chest pain induced by rest, sleep and mental stress, as opposed to exertion.

“A woman might not come in and say, ‘I’m having crushing chest pain, like an elephant is sitting on my chest.’ She might instead say she’s experiencing fatigue, or she might say the symptoms happen because she’s stressed,” Foley said. “And because we tend to think of anginal pain as being pain with exertion, either the patient or the physician – or both – might say, ‘Well, that’s probably not related to heart disease.’”

Women who have heart attacks also present without chest pain more frequently than men, which also leads to delays in diagnosis, particularly among younger age groups, Foley said. Heart disease is the number one killer of women in the United States, yet women often have mild or no symptoms at all until they have a deadly heart attack.

All of which is why women’s heart health is increasingly seen as a specialty area of cardiology, and why it’s important for health care organizations to not only hire female cardiologists to serve women who feel more comfortable seeing a female doctor, but also provide education on the topic in the communities they serve.

St. Charles has a second female cardiologist – Dr. Melissa Gunasekera – joining its staff at the end of March, and discussions are underway about formalizing a women’s cardiology program, said Carlie Gruetzmacher, manager of St. Charles Heart and Lung clinic.

More than three months after her undiagnosed-for-two-months heart attack, Belden is feeling good, and she believes she finally found the right doctor in Foley. That’s not because Foley is a woman, however. It’s because she listens to Belden, adjusts her medications accordingly, and maintains a relentlessly progress-focused perspective about her care.

“I look forward to my meetings with her,” Belden said. “She tells me what she sees and tells me what she thinks we should do, and that we’re moving forward. It’s always, ‘We’re moving you forward’ in a positive way, and that makes me much more comfortable than, ‘We can’t do anything for you.’”

According to Foley, St. Charles schedules more time for her to spend with each patient than any other place she has worked. The benefits ripple out to the patient and beyond, she said.

“Having time to talk to the patient, that’s how you figure out what to do next. It’s just the right thing to do, and it’s nice that (St. Charles) recognizes that,” she said. “It helps you be the person you want to be for your patients. It gives me time to connect with them and to go through their questions and explain what’s going on with them and talk to them about their medications. And if a patient has an understanding of why they’re taking a medication, they’re less likely to stop taking them, which means they’re likely to live longer and feel better.”

She continued: “A lot of women feel more comfortable seeing a woman physician, but ultimately if you’re seeing someone you trust and someone you feel comfortable with, that sets up a good foundation for a good patient-physician relationship, and that’s the most important thing.”

Belden agrees wholeheartedly.

“When I first met (Foley), I didn’t think of her as a woman or a man,” she said. “It was about what she knew and how she made me feel, and she made me feel good.”