A silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic is now up and running in parts of the Bend and Redmond hospitals.

In 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of continuous glucose monitors (CGM) in hospitals to help reduce contact between patients and caregivers and preserve personal protective equipment during the early days of the pandemic.

When worn by people with diabetes, CGMs provide a more robust picture of blood sugar levels than point of care testing, or finger pricks, and have been shown at St. Charles and elsewhere to have life-changing effects on diabetics’ health. Before the 2020 decision, however, the devices were only approved for outpatient use in clinics and personal use.

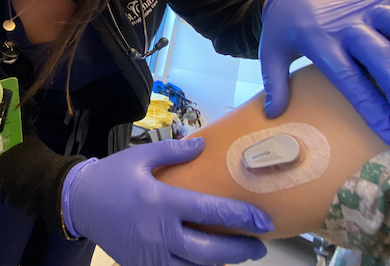

Now, a group of hospital-based clinicians and administrators at St. Charles has launched a pilot program aimed at using CGMs in Bend’s Progressive Care Unit, Redmond’s Medical/Surgical unit and, soon, Bend’s Medical Unit. The pilot was funded in full by a generous grant from the St. Charles Foundation.

Treating diabetes is complicated, said Dr. James Dayton, a hospitalist at St. Charles, but the team’s goals are simple:

“Our goal with any patient with diabetes is to take the best care of them we can to keep their blood sugar at a safe level and to prevent severe hyperglycemia and all hypoglycemia,” he said. “Finger pricks only tell you your blood sugar at one moment at a time. They don’t give you a trend. Continuous glucose monitors take a reading every five minutes to give you a real-time look at glycemic level.”

He continued: “It’s like driving with a windshield that opens a few times a day and then closes as opposed to one that’s open all the time.”

The Dexcom continuous glucose monitors being piloted at St. Charles can show providers if blood sugar is rising or plummeting, how it reacts to doses of insulin, and if it follows a pattern after meals or during a certain part of the day. That kind of information is invaluable when caring for diabetic patients, said Dr. Matthew Wiest, a St. Charles hospitalist.

“This is the next step in the evolution of diabetic management in general, because it gives us so much more information to act upon,” Wiest said. “When you can see the trends you can adjust the medication much more accurately and ultimately treat the patient much more effectively.”

The team has developed an algorithm for caregivers to follow that is designed to help guide decision-making by outlining next steps. During the pilot, continuous monitoring will not replace point of care testing and will not reduce the number of finger pricks for patients, which typically happen multiple times per day.

Fewer finger pricks is a possibility in the future, however, said Don Jacobs, manager of the St. Charles Progressive Care Unit, which would reduce pain for patients and save nurses a significant amount of time. But the potential benefits of a fully implemented CGM program don’t stop at the bedside.

“Patients get to practice with a device in the hospital and learn how it works, giving them confidence to use it at home. And at home, they can teach a family member about it so they can rescue them if they’re having a glycemic event,” Jacobs said. “And the hope is that if they continue to use it correctly that they won’t be readmitted because they’ll be able to see when they’re going in the wrong direction and treat themselves.”

Jacobs and Kelly Ornberg, St. Charles’ manager of clinical nutrition and diabetes education, have been working on adapting outpatient-focused technology for inpatient use. If they are able to demonstrate the value of CGMs to patients, caregivers and providers, they hope to expand and improve the program.

“The way it’s set up works really well in an outpatient setting,” Ornberg said. “The logistics of making it work well on the inpatient side is trickier (but this can be) another really great tool in our tool box and I think it’s really fascinating to see what’s going to happen for both patients and providers.”

Dayton, the hospitalist who has ordered more CGMs than any provider at St. Charles, has already seen the devices make a huge difference in the lives of some of his sickest patients. The pilot program, he said, will put St. Charles ahead of the curve when it comes to diabetic management.

“I think the writing is on the wall that … this is going to be the future of diabetes care at the hospital,” he said. “In terms of how we use them and how we make people comfortable with them, I would rather be ahead of the game than behind.”