When Marinus “Dick” Koning retired in 2008 after a 30-year career as a general surgeon in Redmond, he contemplated what might be the next chapter of his life’s work.

It didn’t take him long to figure it out.

Piqued by his interest in tropical diseases and disorders, Koning traveled to Ethiopia on a medical mission in 2009. Once there, he was struck by not only how many children were born with spina bifida and hydrocephalus (SBH), but also how few of them received the life-saving surgeries they needed. At the time, there was only one neurosurgeon for nearly 100 million people in the country.

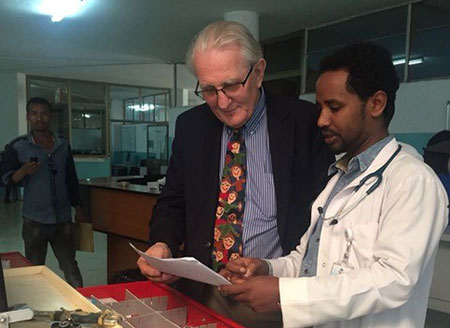

Koning and his identical twin brother, Jan Koning, who is also a retired surgeon from the Nederlands, began performing operations on children with SBH at Korean Hospital in Addis Ababa. But only a small number were fortunate enough to reach the hospital in time to have the openings on their spines closed, or to have shunts placed to drain the water on their brains. Many more suffered and died.

That’s when Koning founded his nonprofit organization, ReachAnother, whose work is to expand the availability of pediatric neurosurgery in Ethiopia as well as develop a countrywide food fortification program. With the support of St. Charles Health System, which donates used surgical instruments, and many individuals in Central Oregon, ReachAnother has saved the lives of more than 5,000 babies through surgical intervention over the last decade.

“An instrument that is not acceptable here anymore because of a divot or tiny crack, in Ethiopia is worth its weight in gold,” he said. “We’ve taken thousands of dollars in instruments.”

In early November, Koning and his team traveled back to Ethiopia, where they’re now working with the government and a group of international public health experts to launch a clinical trial to fortify salt with folic acid.

In the United States, fewer than 2,000 children are born with SBH each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That low number is in large part attributable to the folic acid that, since 1998, has been added to the country’s supply of enriched grain products such as bread, pasta, rice and cereal. In Ethiopia, where unfortified teff is the staple of most families’ diets, more than 40,000 children are born with the birth defect.

Folic acid prevents SBH. The problem, Koning said, is the birth defect develops before the mother is aware she’s pregnant, making it crucial that every woman have access to the vitamin.

“Salt is the only staple food that everybody uses,” he said. “I just learned from a new study that 70 percent of the world population doesn’t have access to wheat or rice or other staple food that can be fortified, so fortified salt has been one of the holy grails of nutrition science.”

But while it has been proven possible to fortify salt with folic acid, it has not yet been proven clinically effective, he said.

“Now we have to do three preliminary studies to show that it can be done and that it’s effective,” he said. “We have no question it will be effective, we just have to show it.”

Koning said the preliminary studies should be completed within the year, after which there will be a “feeding study” to determine whether women who eat folic acid see their folic acid blood levels rise to the desired level. The group will also be evaluating the country’s supply of salt and how it’s distributed to consumers, who “have to like and accept it. (Fortified salt) is a little bit differently colored.”

Koning is hopeful that within the next few years, fortified salt will be a proven method for the prevention of SBH.

“That’s not only good for Ethiopia, it’s also good for the rest of the world,” he said. “It’s amazing that people from Bend, Oregon, now have the eyes of the world focused on them to come up with this solution.”